Remembering Dharampalji

Aug 2021: This is an old article that was written on the request of Pawanji for a publication on Dharampal immediate after his demise perhaps in 2007 or so. Recently with an effort to put together our own experience and understanding based on Dharampalji, we are in the process of expanding and enlarging this note. More coming soon...

When I was asked by Pawanji to write on Dharampalji, I hesitated quite a bit. Not that I cannot or have not written about him, but, with him the problem arises as to which aspect of his personality do I write on – the personal relationship that developed rather tentatively between us in early 2000 and lasted till his death withstanding many ups and downs, or the larger account based on his work, my understanding of the same, its impact, implications and where do I see it all heading. I have taken the liberty that Pawanji granted me, to write as much as I wish and have attempted the impossible, write both accounts. After I finished writing them I realized how much I had to say (and there is more). I wish to thank Pawanji for that, his is one of the best relationships that Dharampalji introduced us to and it has been bonded with the mutual respect and care for Dharampalji.

Personal Interaction with Dharampalji

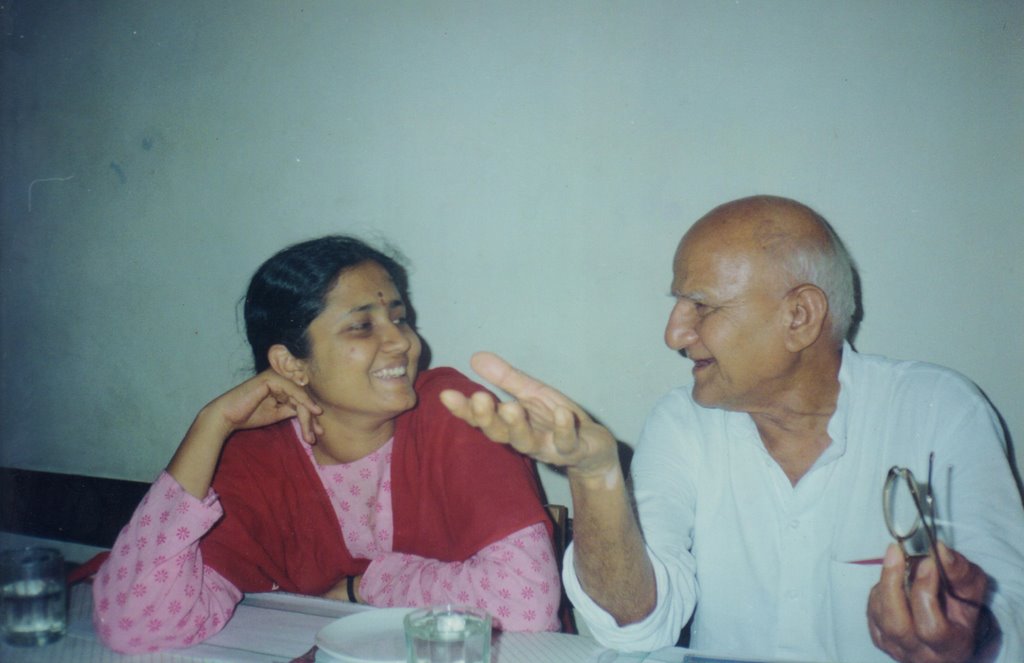

(in this I am also writing on behalf of my wife, Rama whom Dharampalji often called as his youngest daughter)

The first impression of Dharampalji was when I was introduced at lunch at one of our mutual friends’ house. I was introduced as someone who is doing work in Indian management systems. He was nattily dressed, very courteous and listened with much attention to whatever I said, asked a few curious questions. At that time apart from the fact that he was a historian and had written something on history, I wasn’t aware of anything else. I remember telling him that we need to understand our culture and management concepts in them more seriously, etc. How the meeting ended I don’t remember, but, suffice to say that he didn’t pass any uncomplimentary comments or dismiss me off.

First arrival at Sevagram …Encountering The Host

The next time was when Rama and me landed in Sevagram in the year 2000 after having offered to assist him with his work as ‘computer assistants’. It was a March morning and a bit cold for us. There were three people to receive us at the station I remember, we were rather surprised by this. Then as we landed in the Ashram (my first ever visit to the place), we were received by Dharampalji himself. He enquired regarding our travel, whether we had something for breakfast, and that it was rather late for breakfast, however, they had organized some for us. He showed us our room, then told us to always remember to fill up extra water in case water supply stops. Spoke about the truant electricity at Sevagram. Later he took us around the Ashram and showed us the Bapu kuti and other places and introduced to the people at the Ashram. It was only when he took us to the yatri niwas that I realized that he had declined inaugurating an organic farmers' national conference that was starting there that day because he wanted to be available to receive us. The amount of attention he paid as a host had a unique quality - he was like a typical Indian housewife who would go out of her way to ask the guest quite a few times whether everything was fine with their stay, but it also had a certain formal courtesy. I often wondered about this courtesy; was it from his earlier background or was it from his ‘English’ connection? Never asked him though. The first few days were spent in us getting acquainted with the material, with his other works (by then I had managed to read the Science & Technology book though not any other work). Perhaps slowly the magnitude of his work dawned on us. But, more importantly the questions he posed, the information he shared, the insights that he spoke about were all that added further to our understanding or challenging what we thought we understood about this country, its culture, history and people.

I am particular about having a south Indian coffee first thing in the morning and this he realized during our first visit. At Sevagram, the morning milk arrives around the breakfast time, that is by 7.30 or so. But, having realized that it would be good to start the day with coffee, he ensured that there was milk procured the previous evening and that it was boiled couple of times over (though his kuti had quite a few facilities, there was no refrigerator) and we had milk for the first coffee even as early as 5.30 in the morning. This he ensured almost till my last visit. We also gifted him our small coffee filter (the south Indian version) and this was kept washed and cleaned before I reached Sevagram each time. The attention to small details for his visitors was important to him. I have seen him inspect the guest room personally at least couple of times before his daughter arrived to stay with him. Similar treatment was meant for others also. And this was not restricted to Sevagram, even if he were visiting Chennai, he would ensure that if someone were visiting him, that he became the host at that point in time and tried to ensure that with whatever comfort available he made things easy for them.

Working with Dharampalji…The Tough Task Master

During our first visit to Sewagram in 2000, he was working on the Introduction to the Collected writings that were published later that year by Claude Alvares of Other India Books. Once he gave me the text of his introduction and asked my opinion as to how it read. In my naivety, I pointed out quite a few possible enhancements in the draft. He got back to me saying, "now you write something instead of this". My second foolishness was to have accepted this challenge. For some one also going through a crash course on his works, it was too much to chew and obviously I messed it up. When I showed it to him, he started screaming, "No, no, you shouldn’t have come here, you please go back home. You can’t even write, what can you do?" etc. I was furious with him for this, that he shouted at me in front of quite a few other young people who used to hang around that place during those days made it worse (these were azadi bachchao aandalan(ABA) youth who worked out of his spare room), and I walked out of the place. Till dinner I didn’t talk or go anywhere in his direction. Later when I was about to go for a walk post-dinner, he called me from his kuti, "you are going for a walk?", "Yes, Dharampalji’". "Can you bring me some ice cream, preferably, pistachio?" That was his method of making up. He never retained the temporary disapproval or disagreement come in the way of a permanent relationship unless he didn’t value that relationship itself. Always took the first step, in his own graceful way to make up with people. It could be a simple invitation extended through a common friend, a telephone call made by someone else more agreeable to the person, during which Dharampalji happened to be around and will come on line half way through.

Much of our work was to look through the archival materials that were in various envelops, put together those that were connected and relevant and create a compilation. To get them entered in the computer with the help of a couple of local hands whom we hired, compare and proof read the digitalized version and compare it with the original version. Once we did this, Dharampalji would look through the compilation, make corrections and these were incorporated again. At times he would remember and make corrections on the typed piece that was part of the original and which we had missed out during proof reading. While Rama was good in doing this, I was terrible as often the subject matter interested me and I forgot about the proof reading and started to think and talk about its contents. He often chided me saying, "You are not good for doing this". He would always demand that he be given fresh prints of the material, in double line spacing and not any recycled paper. We both hardly ever printed anything, because we were concerned about the amount of paper wasted and in one of our early days with him, when I produced a printout in an already used paper, he told me, "Look I am not bothered if there is a waste of paper, please print it in double line spacing and please do it in a fresh paper and not used paper".

Once I went to his kuti late in the night, perhaps around 11.30 or so to hand over a particularly bulky printout, perhaps about 200 pages of material for reading and correcting. The next morning around 6.30 he was outside our room, calling out for me. When I went out still groggy from my sleep, he was already dressed for his walk. He handed over the bunch of papers to me and said, ‘I have gone through this and marked all the corrections to be made’, and went on, ‘can you incorporate all these corrections and have another print ready for me by the time I am back from the walk?’. Such was his unrealistic demands at times at work, and we got used to it. The year before he died, the morning he landed in Chennai we had our new office pooja, he promptly called me just before the pooja and said, "so when is the pooja?", "10 'o’ clock Dharampalji". Prompt came the reply, "will you be then here by 10.30?". Later days when I started introducing him to email, he would enquire, "why doesn’t your email ensure that the other person replies?".

When he put his mind to finding out some information, he never gave up. His work had to be done and it better be done now. In his maiden visit to the Ulundurpet Ashram (in Tamilnadu) he got curious about some of their records and walked in to their office and insisted that they attend to him. That he was disturbing their regular work didn’t affect him a bit. He wanted to write about their work (which impressed him thoroughly) and he wanted to look at some records, nothing else mattered at that time. Similarly when he wanted to print out the complete catalogue of the India Office Records from the Internet, some of us in Chennai were hesitant, "This would run into a few thousand pages, does he want the entire thing printed?". Of course he did. Similarly, when I had taken to him to the house of the chief priest in one of the prominent temples in Madurai, he was fascinated by all that the person had to say about the governance of the village around the temple. Later when the priest mentioned in passing that there was a book by a visiting scholar (from Britain) on the temple, he became even more curious. He wanted a copy of that book. The priest promised to get it from some elderly uncle and have it ready in a week. One week later Dharampalji was there in front of his door (we had been travelling further down south and on our way back he enquired whether we will be passing by the priest’s place and immediately wanted to visit him), and for the next couple of months, though during this period he was traveling almost all over the country, whenever we spoke over phone, he would always ask whether I had followed up with the priest and got the book. This was the case whether it be the Thuggy and Dacoity records of government of India or the Jati Puranas from the Anthropological Survey or records that he once requested from the Kanchi Math to understand the magnitude of their work. He wanted to understand how things worked and he liked to see some written records if possible and he would persist till others yield to it.

Learning with Dharampalji…The Teacher

One evening Rama who was reading one of the archival documents was rather disturbed and asked, ‘this is terrible and one can only get angry with these people for this’. He smiled and didn’t answer beyond saying, "Just imagine how angry I should be, I have been reading these documents for close to forty years". But later in the evening sitting with a large mug of tea outside his kuti as we did during the summer days (during winter this switched to sessions sitting around his bed with morning coffee mugs or late evening with him tucked into the rugs and encased in the mosquito net) he started on this, "The issue is not to get angry with the British, there is no point in it. We allowed them to come inside to rule us and we sustained them. They did it the only way they knew how to govern. It is their own swabhava. We should understand as to how to have our strength recreated". Like Gandhiji before him, he never held the English responsible for what happened to India. He always held it that we had fallen in bad times and it was our responsibilities to understand what happened, how and why and restore the strength that is inherent in this civilization. Similarly his interest was at a civilizational level.

Those evenings when there was a power cut in Sevagram (Sevagram suffered power cuts like most Indian villages for up to 12 hours in a day during peak summer) the evening talks with him would be much longer. He would talk about history, research, communities, politics, politicians, his interaction with them, how societies functioned, books and which books to read, about trends in the society and what he anticipated to happen, etc. In the process we learnt the intensity with which he tried to understand everything and his endless passion for knowledge.

Morning walks with him was another enjoyable experience at Sevagram (I have also had the privilege of accompanying him for his morning walks in Chennai, Sarnath, Madurai, Kancheepuram, Kanyakumari and Penang). He would start talking about some topic or another and if he got engrossed in the talk, he would stop to emphasize a point, point out an insight or make a declaration or pose a question. The pace could suddenly increase if he remembered that there was work to be done back at the kuti. Often his morning walks meandered to the house of Kanakmalji to sit down and demand a juice from his wife. The two friends did their catching up for the morning, and at times hardly any words would be exchanged, just the newspaper looked through and leave immediately afterwards. He often read the newspaper immediately after returning from the morning walk sitting outside the kuti in his bamboo chair. During summer months this could be under the tree and during winter on the verandah where the sunlight hit directly. It is often here that he also had his breakfast of a cereal or gruel that was his mainstay breakfast or at times the dalia that he managed to incinerate in his small kitchen. He ate them all the same and breakfast was the least interesting food for him as it always went with the newspaper. He never spent too much time with the newspaper except if there was something that caught his eye. He received a large number of newsletters, journals and magazines. Many of them never came out of the jackets or envelops in which they were delivered. I once asked him about this and he replied, ‘what can I do knowing all this, if I can do something then it is fine, but, I cannot do anything and I don’t want to crowd my mind with all kinds of information, I don’t have that kind of time’. He knew his sharpest tool was the mind and never even casually indulged in anything that could bring down its sharpness. He was careful as to what occupied his mind time and never wasted his mind in issues in which his understanding was not much or he couldn’t do anything. This also extended to whom and how much time he spent with people. Though he would not stand loose talk with most people, many times some of his own chelas would use his presence for just that, but, he didn’t mind, for him certain rules were relaxed for certain people. Later days of course this too made him tired.

Excitement To Share, To Communicate…The Friend

Whenever he found something that caught his interest, then immediately he would make a number of copies of the material, he wrote a note to go with the material outlining what was the significance of this material and it was sent by post immediately. He got excited about certain books, new developments, some political situation, news he had read, etc. and always ensured that he shared it with a few friends, the few could at times be as large as 25 people and at times just 2. The frenzy of activity that had to happen at Sevagram for him to get this much done was rather high. First he wrote several drafts of a short note to be sent, then he decided who will receive this and decided the number of copies to be made. There were always a few extra copies that were retained with him in different files and under different categories. After this the addresses had to be written in the envelops and someone had to go to the post office opposite to the Ashram to post the lot. Firkeji (I hope that is his name, I never got it right) who was in charge of maintaining the place around the kuti often was the chosen deliverer of the mails to the post office as well as the carrier of letters from the post office to the ashram. This process at the Sevagram Ashram could take about two to three hours, the photocopy machine at the chowk will not work, there will not be adequate envelopes, the letter could not be typed at times for an entire day, ...but, he would not rest till he received the final word that the letters have been dispatched. All this changed when we introduced email to Dharampalji.

Emailing was a very difficult proposition at Sevagram. During our first visit we carried a modem and tried to connect it with our computer and the telephone line initially in our kuti (with more than 100 mts of extra telephone wire drawn from one kuti to another, this itself raised much curiosity and eyebrows at the ashram) and later on at the ABA office. Sevagram connected to the Nagpur server and we had to dial a Nagpur number to connect to the Internet, and the connection was uniformly bad. Except for us no one in the Ashram was dependent on the email, hence never understood what was this all about. But, once Dharampalji understood the speed of email, he got very fascinated by it. Despite being explained many times he failed to understand as to where the emails that got lost in transmission exactly ‘go’. He suspected that these were perhaps stolen by someone en route. Once he understood the speed of emails, he always got what he wanted to be sent to people typed and sent as email. While I was in Chennai, there will be a phone call asking me whether I have received the email within fifteen minutes of him sending it. If one didn’t get back to him with comments then there will be a call the next day yet again. This was the advantage of technology for him, ability to reach people with information fast and elicit their response. He never mastered the computer though, it seems he tried sometime in the early nineties, but, later on it became too much for him and this technology baffled him. Particularly this opinion was furthered by the thoroughly unorganized method in which his computer work got done thanks to the never tiring efforts ABA friends at Sevagram, who were all self-thaught and never stayed for long. He assumed that the computer gobbled up quite a few of his writings, that there were ‘worms’ in it which would eat up data, that the ‘email number’ (which is how he referred to email address despite being correcting many times) of people were not properly given, etc. After repeated attempts by us to show that it was because of how things were managed at Sevagram, he did realize that there could be problems and any later date complaint about the computer in sevagram, at least to me, would be qualified with, ‘you know these people don’t know how to handle this machine’ .

In the last few years, he would email many things, if he was impressed by a book, there will be a extracts from the book (he would mark it in the book, get it typed, proof read it and make corrections twice over before it was sent) along with note from him as to why he thinks this is important, it could be an article that he had read which was interesting or a news item, they were all sent across. At times when I got to be his messenger (particularly when he had sent such mails from Chennai, which meant that I took down notes from him and then sent the email from home) and read out response to him over phone, he would still demand that he be given a ‘print’ of the response. It made him feel better to read responses himself on a paper. He liked when there was a critical response or a well thought out response. His respect for his friends would come out during those instances. I remember a rather cryptic dismissive looking response from one of his popular followers for his writing on the arrest of the kanchi acharya. When I read it out to him, he said, "Oh! That is what he thinks!!, then he must know something that we don’t!!" To me it may have looked like a dismissive statement, but, to him it was not. He thought that his friends never indulged in writing to him without seriousness. The written word was serious business for him, he weighed each work, each letter almost, and expected it of everyone else too.

Motivating People to respond to Society…the Leader / Mentor

"Why don’t you do something about this?" was one of his favourite questions. "This" could simply be the frequent power shut down at Sevagram or a more complicated arrest of the Kanchi Shankaracharya. For him lack of response from the people around him on any social issue was a matter of concern and regardless of the magnitude of the action warranted in the situation (which he would certainly talk about), lack of action of any kind bothered him. A corollary to this is his other frequent comment, ‘yeh log kuch nahi kar sakte’, these people are not capable of doing anything. This at times would be modified as, ‘inse kuch hoga nahin’. (Nothing can be done with these people) This was the worst comment that he had said sometimes about some of his close friends. The strong comments were never for his own people, he could indulge the members of the former PPST on all issues forever whereas he would not tolerate even a for awhile someone else at that level. Apart from that he would casually and in lighter vein call ‘a fool’ almost everyone though even to this rule he had exceptions. Among his friends, "Girija and MD" were never addressed as fools and he once told me that he cannot call that of Rama either. His sparing of time for youth of ABA also had to do with the sense of them 'doing' something. Whenever Rajiv Dixit arrived at the Sevagram ashram, Dharampalji's kuti will be out of bounds for all others, it may be for just few hours or it may be for couple of days at times. Rajiv was travelling all over the country lecturing, campaigning and it was important for Dharampalji to be available for him. At times he could also spot talent very early. I once took a group of young people with different backgrounds to meet with him in Chennai where he was staying and at the end of two hours with them, he told me to keep an eye on one particular young woman. 'She would do something, I think!'. In the next few years, she rose in her career, travelled across the world and on return took monatic vows and initiated many ventures in her monastry even as a young novice!

‘Why don’t you write something on this?’ was his other favourite question. I was particularly addressed this question whenever I told him over phone some interesting news or other. He would be surprised that he was not aware of this, pose a few more questions and then will come this inevitable question. I realized that this question he posed to many of his closer people. For him on any subject people should be able to write easily a 10-15 page note if they knew something on the subject. It was same for everyone, someone serious like Balu in Chennai or a young person to whom he was introduced such as Priya, would both get the same question. I often thought this was his method of addressing one of the problems that he thought Indians have, viz., that we didn’t write very frequently and certainly not adequately. Any subject if one were to express oneself as an serious pursuer should be able to write a few pages on the material, if it happened to be something more serious then it should be longer. He was proud and fascinated when his grand daughter once sent him a note she had written which was long, perhaps about 50 pages. He said that this was a tradition in the west, particularly Europe that we ought to learn from.

Just like his anger with people, his appreciation too was instant and could be overwhelming. Once I had picked up a speech by the outgoing Malaysian president to a larger Islamic body that looked interesting and forwarded it to him by email. After having read it, he immediately called me to praise the piece. 'That was very nice you picked it up, I am sending it to all these Delhi fellows, they don’t seem to be aware of it'. This went on for the next couple of days. It seemed that he had been in touch with quite a few people in Delhi and they were all ignorant of the fact. With much pride he said, 'Arrey what this fellow picked it off the Internet and you are not able to get it with your own people sitting in the foreign office there’, he said to them rather proudly. Similarly, when we received the CD containing the posters of the exhibition on Gandhiji that was put together by Pawanji and Anuradhaji of SIDH along with his daughter Prof. Gita at Heidelburg, initially he was rather relectuant to look at it. But, once he saw the presentation and the quotes of Gandhiji they had chosen, he was completely excited. Immediately there were phone calls to congratulate and proposal that this should be brought out as a book in India! He would not stop working on it till eventually it did get published as 'Quintessential Gandhi'.

In Love with Life…the Connoisseur

It was no secret among his friends that Dharampalji loved good food. Few also knew that he enjoyed good literature and also a very selective taste in music. He had a tape recorder in Sevagram which would play at times the same tape all evening and through the night whenever he fell asleep or the power finally gave the recorded some relief by going off. He listened to western classics such as Mozart and Tchakovsky and particularly the record that were sent to him by his two grand children (they had specially recorded some music for him and he was proud of it). He also listened to Hindustani and Carnatic classical from India, but rather choosy about what he listened to. Morning times one could listen Shilpa Shodalikar, a Marathi bhajan cassette in his kuti. During our fist visit I had carried much music and after he caught sight of all the cassettes, he enquired about them and then listened to a few, he was completely bowled over by the voice of Lakshmi Shankar an elderly Hindustani singer, whose thumris I had a collection of. The first time he listened, he got back to me with further request and enquired about her background. All I knew was that I liked her music and nothing else, but, the next morning he had read through the blurbs of the two cassettes I had given to him of her and told me all about her. ‘She has a traditional Indian voice, perhaps this is how music used to be sung few hundred years back!’ came a startling revelation! I started to listen to Lakshmi Shankar with a new respect from then on. Similarly, when he listened to the Bengali folk tunes of Mahesh Ranjan Shom, he demanded that I make a copy of all the cassettes I have of the artist for him.

I always experimented with him in terms of taking him to different restaurants in Chennai. It was a risk and always mixed with an apprehension. He approved of some, disapproved many and generally an evening out with him in Chennai could be a rewarding experience or a nightmare. He appreciated good food, but, not too much variety. He was impressed by a small road side restaurant in Madurai, but, when I took him to a restaurant where they promised about 40 varieties of Dosa in Chennai, he was disappointed. "All this is modern, what is in so many varieties, no, no, I don’t think they can even make one variety in this very well, this is all too silly".

He had his favourites, Woodlands, The Mathura Restaurant of the Woodlands group in Mount Road where he had lunched often during his working days in the madras archive – it was in the mid way between the state archives and the MLA hostel where he was staying those days, the Eden at Besant Nagar which he claimed he had ‘discovered’ along with GSR one hot summer day wandering around the place. He approved much and promoted a little coffee shop run by Gujarati brothers in the music college. He complimented the owners, enquired to them about their background and how they ended up setting up a coffee shop in Chennai, etc. Similarly, the methi paratha and sarson ka saag in a Punjabi restaurant elicited much interest, but to his utter dismay, he found that the waiter was a Tamil, the chef from Orissa and the owner of the place was a Keralite and there was not a single Punjabi soul in the restaurant! Similarly when he walked into the Chola Sheraton looking for an Ice Cream place that he had had good ice cream a decade or so back, and found that they had shut down the place, he was rather disappointed. He called someone senior among the staff who remembered the old place and immediately launched on an enquiry about when the changes had taken place and expressed his disappointment and that he didn’t feel like ordering anything now from the reduced menu card. By then the entire set of staff were loitering around his table and we had an entourage of them apologize, chat in a friendly manner and see us out to the door. He had a way of smiling and disarming the most disapproving waiters one encounters in some of the fancier restaurants. He joked often at his own cost to ensure that they immediately start to cater to his needs. We have often been enquired about him by waiters at the Woodlands restaurant, though they would confess that serving him was always difficult because he demanded so much more and yet they felt happy to be serving him.

I should mention Chaya here, she was his newly employed cook in Sevagram when we first reached there. She hails from a village close to the Ashram, I don’t know whether she would be requested to say a few words about her favourite ‘Bhayiji’. She had mastered the art of adding that little bit of salt, that iota of oil for his cooking and was always willing to spend the extra 10 minutes to make a halwa for him whenever he had a sweet tooth and demanded the he be fed halwa on that day. She also was his in-house counselor, who advised him on his health and at times took the liberty to warn him on his wayward ways in eating whatever people brought when they visited him, she was almost a daughter. After his death, when I asked her what did she cook for him, she was proud to say that she had made his favourite halwa a few days before and he liked it.

Literature too, he had a good taste of. Unfortunately, I didn’t have much to share with him on this aspect. He would appreciate good Hindi and English literature. I remember he appreciated the ‘Sahasraphan’, a translation of a Telugu (or was it Sanskrit work) by P.V. Narasimha Rao, the former Prime Minister of India. He said that this man mush have had something in his genes for the subject for him to be able to write like that.

Coffee for us at home was a specific blend of particular seeds, roasted and ground and the decoction made with the south Indian filter. When I first introduced my home blend to him during my stay at Sevagram, he was taken with it and since then whenever he wanted good coffee, he would say, "Why don’t you come over and bring some coffee, if you don’t do anything here at least you can have the benefit of bringing the coffee", or simpler, "Why don’t you send some good coffee?". This is some thing we did for the remaining years, on and off. A week before he passed away he had called Rama and asked her to send him coffee again. To her utter regret this is something that we could not send across in time.

Pride and Prejudice…The Doting Parent (and Grand Parent)

He was certainly proud of the small achievements of his close associates and will go all his way to defend them forever. His closest association was with the PPST people and he was very proud of them. He often said that they were the strongest group of young intellectuals getting together to do something in Independent India and often repeated that some of them were Prime Ministerial candidates. He was very proud of their achievements like a doting father. He could indulge them forever as he could never say no to them. The dis-functioning and eventual end of PPST as it was known, was perhaps one of the biggest disappointment in his life. He often tried to analyse it, criticized them all for getting married, having children, etc. but, I don’t think he ever objectively assessed them. He was too much biased towards them and could not stand others criticize them in front of him. He had repeatedly chided some of the senior PPST members for not nurturing new talent, for being too high in their expectations, etc. but, these were mistakes that can be laid in his door too and he was aware of it.

Similarly I remember his first meeting with Priya, my younger colleague at Samanvaya. She was so radical and different and asked such interesting questions, he completely got overwhelmed and immediately proclaimed her as his grand daughter (she must be the same age as his grand daughter in Germany), and from then on he would go all out to ensure that he spent time with her and encouraged her. He was touched when Priya once gifted him with a Tamilian dhoti and angavasthram for a Deepavali he spent in Chennai. He immediately wore them for her and retained that dress till she left.

Contrary to his image that he always assessed people before accepting them, I think he always took to people instantly first and then built the reasons for it, like many ordinary mortals.

Comments

Keep on writing, great job!

Keep on writing, great job!

Hello there, I found your…

Hello there, I found your blog by means of Google even as searching for a related subject, your website came up, it

seems great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Fine way of telling, and…

Fine way of telling, and pleasant paragraph to obtain information on the

topic of my presentation subject, which i am going to present in institution of higher education.

Add new comment