This article was written for Teacher Plus magazine December 2022 special issue on Climate Change. The magazine maybe accessed here.

Naming the elephant in the room or even parts of it

Climate change teaching in practice

Climate change response is deliberately defined as a phenomenon of global magnitude in which the small individual acts don’t really add up to anything significant. Similarly, teaching climate change and sensitizing the next generation is made into a theoretical lesson that cannot hold their attention for long. In this article I will try to provide practical exercises that I have tried with various groups – students, rural women, farmers, government officials, etc., over a period of time to create climate change awareness and action. I am sharing this especially for teachers who are concerned and are trying their best to make their students aware and bring some response as part of their daily practice.

Fear is the worst way of sensitizing people to climate change. As the consequences of climate change across the world, there is daily news from permafrost melting, biodiversity losses, amazon forest fire, lack of immunity, plastic in the blood stream, and much more. Often, the need to create awareness is bringing into focus all these issues and making the audience relate to the same. Most people today have access to this information, but, the magnitude of the challenge, the immediacy of the need for action and the need for everyone to participate are the key missing elements.

The magnitude of the challenge can be brought to focus through time series presentations. I have taken a 24 hour news cycle of climate change impact from diverse parts of the world and presented as a series of slides with a ticking clock across the slides to inform everyone that this is just one day and that such news is reported every day from across the world. Similarly, providing data on the number of species that have disappeared since 24 hours, or the amount of land that has been submerged under the sea, or the number of glaciers that have melted, or the area of forest that has been cleared, often gives people the immediacy of the need for action. Such data is available online and can be quickly compiled within a short duration for teachers.

The challenge arises when we are asking people to act on climate change. What can anyone do to mitigate climate change? It seems like a daunting task and often looks like much of the work has to happen from the government and larger agencies rather than the individual. This is even more so in the case of students. Despite the global media profiling Greta Thunberg, we don’t see such consistent student awareness movement in India, leave alone protest. A statement such as ‘’How Dare You?’’ directed at global leaders which got her profiled globally, if uttered by any student in India against any national or regional leader would have resulted in the student being disbarred from school and perhaps ostracized from immediate social circles. This is a reflection on us as a society, which is far less tolerant of criticism, particularly when it comes from people younger than us. This is something we need to reflect upon, though not the focus of this article.

So, students are left with only the option of examining their own lifestyles, analyzing and understanding their own circumstances, and perhaps initiating some action locally that can help address some environmental issue locally. In the following section, I have profiled a few of such simple exercises that help them to understand the larger issues better and in the process perhaps become more responsible towards the planet.

How much did the cake travel?

It was a black forest cake and we had just finished it off. This is how, one day, my class on Green Economy started. A batch of fresh graduates had joined the Masters programme and they were celebrating by cutting a cake. One of the students was a baker. She listed all the ingredients that went into the cake and where they are produced and the distance they travelled to arrive at the cake shop from which it was bought. Until then, we had assumed that all the ingredients came directly from the places they were grown in the same form to the cake shop, often this is not the case, sometimes materials are grown, minimally processed and packaged in three different locations (even countries) before they are sent to the place where they are baked together. When we calculated the distance all the ingredients travelled, we realized that they must have travelled not less than 2200 kms to become the cake that was available at less than a 2 kms distance from the college. This led to a discussion on the consumption of food grown locally and how much we are unaware of how far food travels to reach us, particularly in urban centres. None of the students forgot the simplified ‘’food miles’’ calculation we did that day and even now remember it every time they eat a cake.

While carbon emission is difficult to comprehend, consumption is easier to understand as a personal daily life occurrence. We are all consumers.

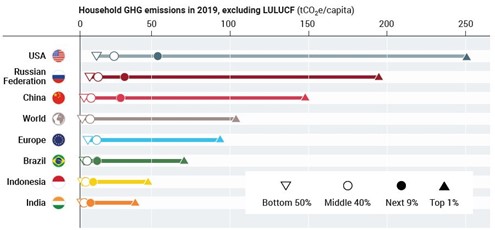

Being consumers in a global market means that we are contributors to the global phenomena of carbon emission with or without our understanding. Complicated calculations are often made about carbon footprint that we leave on the planet and how much per capita carbon emission is made by countries. An oft repeated lullaby for us is that India has a very low per capita carbon footprint in comparison to other countries. That is deceptive if we disregard the size or massive inequality that prevails here. The urban rich in the country often consume more and contribute at par with the rich in other rich countries. The politics of inequality and how some people are retained poor for the sake of other people remaining rich is something that every society has been practicing for a long time in various ways.

How many plastic bags do people carry?

In a simple observation exercise the students did, they visited shops in residential areas of diverse economic strata and standing outside the multi-purpose kirana shop (increasingly called the local super market), they observed how single use disposable bags were carried out by each consumer during a period of busy business hour from the shop. Invariably, it was found that the richer neighbourhoods had people carry more such bags when they left the shop. This experience when shared in the classroom led to a discussion on the relationship between inequality and waste generation and how there is no moral superiority as a nation for less per capita waste generation.

Can we refuse packaging?

Why do we even pack things? If we are buying and carrying them for a short distance, what is the need to pack them? For instance, most pens that people use are made of plastic (bad enough), they have inks sometimes in single use plastic refills (worse) and then they are wrapped in a plastic box (single use and I haven’t seen anyone have any other use for it), which is then wrapped in another plastic cover, and over this, the retailer may give you a plastic bag to carry it home. Out of these, except for the pen (and refill) everything else is just single use non-decomposable waste. Absolutely useless, and if refused and given back, the shopkeeper has the responsibility to take it back. Students can be encouraged to carry their own cloth bags and remove such excess plastic bags when they are shopping and return it to the retailer with the message that, ‘’we are only paying for the product, not the waste.’’ This is an individual choice and can be easily done at the level of the student.

What’s our knowledge of biodiversity?

Simple exercises that can be undertaken anywhere include collecting diverse types of recipes from homes of the same dishes and sharing it in a classroom, or collecting different plants and making a note of their properties and stories from different regions. While the latter has been effective for us with the village women, the former may be easier for urban schools. It is easier to observe the diversity if one were to identify the one or two ingredients that are specifically added to the same dish in different regions. I often ask the 3rd and 4th generation urbanites to get the recipe from the oldest member of the family as otherwise it tends to get universalized.

While such an exercise provides for an interesting discussion on the diversity in terms of food, it is important that the same is linked to the raw materials to showcase their diversity as well. One of the exercises is also to list all the raw materials that go into any dish and where they come from (similar to the cake exercise). In Europe, I knew a university researcher who did not know the ingredients that went into the dish he ate almost every other day. Food is the direct link between us and the Earth, if we fail to recognize the raw materials that go into making a dish, we lose the basic sensitization to food and Earth. I have also realized that the ways in which we acknowledge the raw materials is also important. For instance, there is a disturbing tendency to name a chutney as white, red, or green based on the colour rather than as coconut, tomato, or mint based on its ingredients. While this seems negligibly small, this is the beginning of the loss of sensitivity to diversity in our daily lives.

Of course, if schools or education institutions have their own spaces to grow traditional varieties of vegetables, greens, or fruits and can gather and narrate stories and uses of these crops, it is a direct route to understanding biodiversity. It is important for the students to be sensitized to the diverse nature of these crops and seeds and their contribution to the nutrition and health of humans.

In the post-pandemic situation, emphasis on immunity building through diverse food inputs needs to be highlighted as well. Students can easily be encouraged to grow small potted plants in their homes and exchange notes and photos of their potted plants with each other.

While the understanding of biodiversity is not usually prioritized, it becomes worse in the case of social challenges. The World Economic Forum has listed social norms and disappearance of biodiversity as two of the biggest risks for the current decade. Today, it is globally recognized that environmental justice cannot be divorced from social justice. Among school children, inequity becomes difficult to explain, particularly if they come from privileged communities and groups. Many cannot comprehend someone not having what they have taken so much for granted, that they don’t recognize is a privilege. One of the exercises that we have carried out with first year engineering students is to explore this.

Can we understand the motivations for the injustice we have encountered?

In one session, the students were asked to list their reasons for taking the engineering course (information technology engineering). Most of them gave reasons such as jobs being easily available, easy work life, high salaries, etc. In a second session, they were divided into groups and asked to discuss any form of injustice they may have encountered and why they thought they were subjected to that injustice. A few instances of injustice that they listed included being fined for travelling a short distance without a helmet while those with connections got away, being denied an award because another student was given priority, etc., The groups were then asked to analyze and list the motivations of the perpetrators of the injustice. They came up with – easy way to earn money, lazy ways of earning money, etc. When it was pointed out to them that this was similar to their own motivations for joining the engineering course, the students paused. It hit them for the first time that while they were not aware of personally having caused injustice to anyone, the fact that their motivations had something in common with those who were (in their own eyes) causing injustice, could mean that they could also be contributing to injustice in society rather than creating a just society. Such exercises provide students with not merely appreciation of issues related to social injustice, but also environmental challenges and climate change vulnerable communities and how looking at issues from the prism of prevailing injustices could influence their own understanding.

Calculating food miles, carrying one’s own water bottle and refusing to purchase water sold in plastic bottles, refusing excessive plastic waste generating packaging materials, developing an appreciation of biodiversity and based on it the health and nutritional benefits, understanding climate justice by examining their own lives, are all possible ways of developing sensitivity towards climate change. Today, more than ever, it is in developing these sensitivities that we have hope. Such sensitivities result in responsible acts of consumption and lifestyle and these acts result in countering the impact. As a civilization that has had the longest continuous existence, we are inheritors of a longstanding capacity to sustain and prosper. Becoming sensitive and aware of the issues through experience and examination of our own life provides us with the capacity to innovate, create, and invoke the sustaining nature within our own civilizational ethos. In doing so, we build courage, confidence, and conviction in not just our future generation, but also the rest of the world.